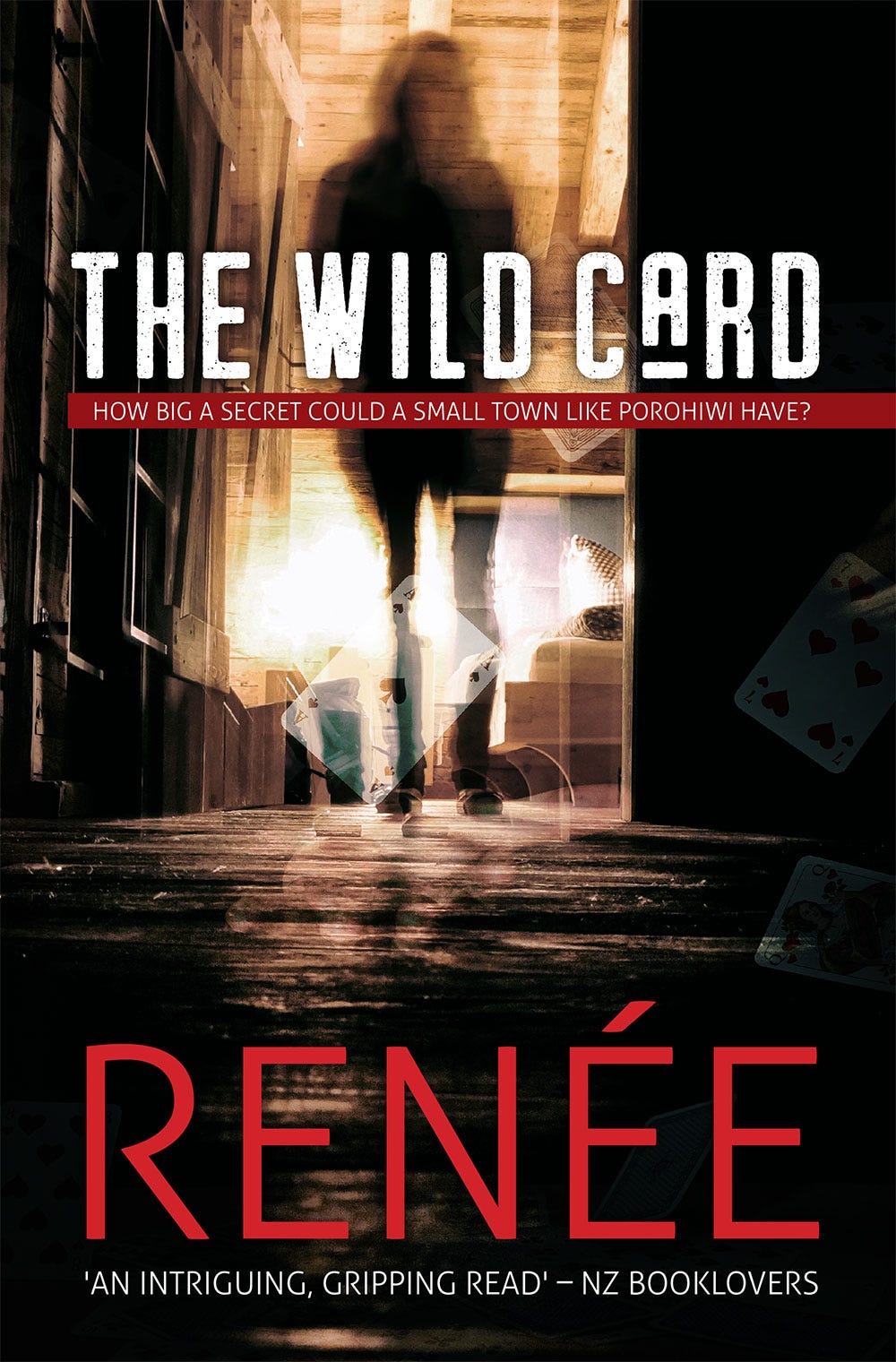

Losing both looks like carelessness

An unforgettable heroine rethinks family and community in this New Zealand novel

Reading this book feels like hanging out with an old friend. I’ve read it all the way through twice and each time, at the end, I wanted nothing more than to be able to get a coffee and some cake and shoot the breeze with the main characters. More specifically, I want to go to the Mimosa Café in fictional Porohiwi, just outside of Wellington, New Zealand, and soak in a community that now feels familiar to me.

The Wild Card follows a classic formula: a middle-aged protagonist digs into the past to solve a mystery, leading to peril and a new reckoning. Here, it’s 37-year-old Ruby, who was left in a kete (a Māori carrying bag) at a local children’s home in 1981. Ruby wants to solve the mystery of her origins—all she knows is she’s of Māori and European heritage. But she’s also carrying another mystery: what happened to her friend and protector Betty, who was found drowned outside the home aged just fifteen? To answer these questions, she has to return to her hometown and face the truth about the past—as well as the reasons for her failed marriage.

Too often, this is the set-up for a prurient melodrama. The Wild Card completely refuses that exploitative approach. Renée is unflinching about the institutional violence Ruby and Betty suffered, but she’s also sparing. The point is that this happened—the point is the failure of New Zealand’s government to do anything to prevent or address the systematic abuses within its institutions, abuses that were entwined with the oppression of Māori people. This history has echoes around the world, from Australia’s history of removing Indigenous children from their homes to North American residential schools and Irish mother and baby homes.

Instead of voyeuristic depictions of violence, we get the mundane reality of what it’s like for Ruby to be a trauma survivor, relayed with her characteristic wry humour.

If she got hungry and there was no food, she got anxious. The anxiety turned to irritation in a heartbeat. It also made her deeply annoyed with herself.

Early in the book, Ruby’s apartment gets trashed. She agrees to talk to the police office but refuses his request to be interviewed at the police station:

Her response was immediate.

‘No. I’ve done nothing wrong. I’m not going to the station.’

Through such small moments, the minute nuances of human interactions, Renée creates a believable world able to move from misery to hilarity and joy without missing a beat.

Although Ruby is heterosexual, this feels like a very queer novel to me. There are several queer characters, but it’s not just that. Ruby is rooted in overlapping queer communities, her real inheritance from her lesbian-feminist mother Kate, whose death motivates Ruby’s dive into her personal history. Having fled from the children’s home on the night of Betty’s death, Ruby was taken in by Kate, who adopts her and assembles a motley collection of co-parents to help in the classic tradition of queer kinship.

As a result, Ruby returns, not to the family home or to a standard cast of relatives, but to her mother’s main community: the local amateur theatre company, The Porohiwi Players. In the novel, Ruby is doubly involved in the Players. She’s starring as Lady Bracknell in a new production of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, which supplies each chapter with a witty epigraph. She’s also researching the Players’ history for a book. I especially enjoyed that aspect, because I’ve done exactly that myself, with a company much like the Porohiwi Players. The Bournemouth Little Theatre Company, too, was formed just after the First World War, part of the wave of amateur theatre companies that flourished in the 1920s and 1930s. I was working on a book about Dorothy L. Sayers and her friends, one of whom was Dorothy Rowe, a co-founder of the Bournemouth Little Theatre Company.

Like Ruby, I spent hours going through the programmes and news-clippings and old ticket stubs and other bits and pieces that make up a theatrical archive (although fortunately I only had to ask the Bournemouth Library for access, not navigate my ex’s family dynamics, like Ruby does). Later on, I got to attend the group’s centenary celebration. Just like in fictional Porohiwi the legendary productions, the back-stage stories, and the everlasting valiant struggle to make it to opening night form a kind of glue, transforming disparate people into a kind of theatrical family.

In her acknowledgements, Renée mentions the first piece of feedback she got on the novel: “Too many characters, Renée – cut some.” I won’t lie: there are a lot of characters, and sometimes I wanted a chart to track of them. But I wouldn’t cut a single one, because they make the novel what it is: an homage to community, with all its warts, all its dysfunction, and all its capacity to save us even when—especially when—we can’t save ourselves.

Renée and I appeared separately on Caroline Crampton’s wonderful Shedunnit podcast. I spoke about Dorothy L. Sayers and her friends, Renée confessed her love for Sayers’ Gaudy Night, and Crampton introduced us. The power of community continues! I read The Wild Card as an e-book purchased from the publisher. You can find out more about it and how to read it here.